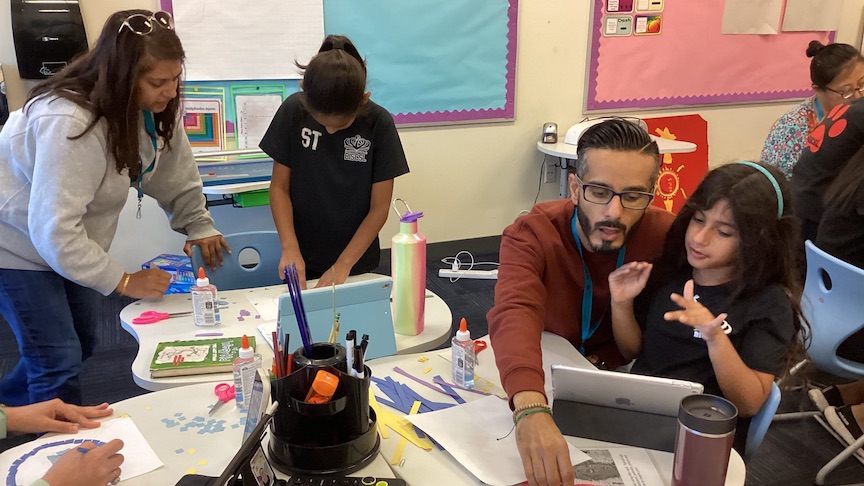

My child’s been diagnosed neurodivergent. What now? Our latest #NAEInsights feature looks at neurodiversity with guidance from experts on how parents can provide the support children might need.

School was not easy for Adam Neale. He was diagnosed with dyslexia at age nine, and received an ADHD diagnosis much more recently—about a year ago. Neale grew up in England in the 1990s, and he says that at the time educators and school systems were not well equipped to support him socially, emotionally or academically.

Today, Neale is a Learning Support Teacher at St. Andrews International School in Bangkok, Thailand. He’s a fierce and joyful advocate for neurodivergent children, but getting here took help. To make sure he got the education and opportunities he deserved, his mother went back to school and became a Learning Support Specialist.

Parents “have to become advocates”, Neale says. “You have to be that voice because unfortunately we children can't always express at that age, that level of cognition.” That does not mean that all parents have to train to become Learning Support Specialists. It does mean figuring out what resources your child needs and securing those.

One of the most fundamental ways to be an advocate for your child is to fully embrace the idea that they are intelligent, capable and eager to learn. A neurodivergent diagnosis, and even difficulty in school, can lead to a successful future. Richard Branson and Charles Schwab both have dyslexia and Branson dropped out of school at age 16. How we talk to kids, and help them envision their futures matters. As Neale, another neurodivergent success story, says, “I'm not those labels that people put onto me. That was their speculative labelling of my ability rather than what I can do.”

Things are better than they were when Neale was growing up. Neurodiversity has become more widely understood as a way to think about how different types of students learn and behave in the classroom. It has become far more common for schools to identify neurodivergent students and address their specific needs. This process has improved as rates of specific diagnoses have increased.

This is not necessarily because more children are neurodiverse. The kid who constantly interrupted your elementary school classroom with well-meaning but ill-timed jokes, who couldn’t sit still? Today that child might have an ADHD diagnosis, and social, and perhaps pharmaceutical, support to go with it. The way we think about autism has changed drastically in less than a generation, from a particular class of largely non-verbal children, to a whole spectrum of behaviours with both challenges and strengths coupled with specific interventions and encouragement.

But in spite of growing awareness, educational resources are unequally distributed within countries and across schools. The number of students who may benefit from targeted interventions is still a substantial minority.

This is why parents play such a significant role.

What is neurodivergence, and why didn’t we hear about it growing up?

Neurodivergent in and of itself is not a medical term or distinct diagnosis. It’s a way to talk about how some people form thoughts and process information, emotions, and interactions with others, without stigma. Neurodivergent means that your brain works a bit, or, in some cases, quite a lot, differently from most other brains. Neurotypical means your brain is more, well, typical. And neurodiversity is a way to talk about the entire range of human intellect without a hierarchy of better and worse ways of thinking and interacting with the world.

Judy Singer, an Australian sociologist, is generally credited with being the first scholar to use the term, and to use language to describe intellectual and emotional differences as natural variations, rather than deficiencies. She is also individual proof of concept—Singer, who is on the autism spectrum, came up with the term neurodiversity in an undergraduate thesis in the late 1990s.

Estimates on how widespread neurodiversity is vary. In a 2020 article in the British Medical Bulletin, Dr. Nancy Doyle, an organisational psychologist who focuses on neurodiversity in the workplace, estimated that 15-20% of all humans, including students, are neurodivergent in some way. Specific diagnoses range widely, even within broad categories like autism spectrum disorder and attention deficit disorder. Children who have dyslexia and dyscalculia, or difficulty learning numeracy and maths, are also considered neurodivergent, Some developmental, sensory and mental health issues, including Down Syndrome, Tourette’s Syndrome, bi-polar disorder and some forms of anxiety are also considered neurodivergent diagnoses, among others.

Just as neurotypical learners are not all equally skilled at solving quadratic equations, learning French or making persuasive arguments, neurodivergence can take many forms. Some kids are non-verbal. Others are verbal processors who tend to disrupt the rest of the class to share arcane details they ferreted out of a history lesson, while also struggling to learn how to read fluently.

You will need to communicate clearly and often with your school to help your child’s teachers fully understand their needs, some more often than others depending on your child’s abilities and interests. As a parent you’ll also need to make sure you understand how the school functions, who to turn to for enrichment opportunities, counselling, or a more intensive intervention if what’s going on in the classroom isn’t working. Working with, rather than against, the school to make sure the classroom is a place where everyone can learn to the best of their ability may take some time, more so in some places than in others, but it’s the first step in advocating for your child’s individual learning process.

Neurodivergent children, and their parents today have more resources at their disposal than when Neale and his mother were navigating the educational system, figuring out how to be an advocate for a neurodivergent child is still challenging. Here are five ways to support neurodivergent learners, in the school setting, and at home and with peers from Nord Anglia teachers.

1. Know when to advocate and when to step back

As parents, it’s natural to want to protect our children, especially when they are facing hardship. One of the toughest things to learn with any child, but especially with one who is neurodivergent, is when they need help, and when handling a situation on their own can actually be a learning experience and confidence booster.

Neale remembers this experience from his own education. “I watched my mom stand up for me,” he said. “But in hindsight, some of that had a negative ripple on me because I was hearing ‘Oh Adam can't do this or Adam gets troubles with that.’ So it's knowing when to step in and say, ‘Well, this isn't working for my child. I'd like you to develop more sensory friendly environments,’ or ‘I'd rather have you be more flexible in their routine,’ but also knowing when to not have those conversations.”

If you’re concerned that your child’s physical safety is at risk, always err on the side of weighing in. But if they’re involved in a normal playground dispute over who’s next in line for the swings or whether someone was cheating? Give them a chance to handle it on their own.

Kids need to know you are in their corner. They don’t need you to solve every problem. It will be a trial and error process.

2. Customise their learning experience

Most schools are structured for neurotypical students. And yet even for them, the system doesn’t always work. “Each person is so different,” Neale says. “I think this is why bespoke education is probably going to be the future of education, rather than this industrialised view of what we consider education to be.”

So what exactly does bespoke education mean? Getting to really know kids and their interests for one. If a child is really into wrestling, Neale adorns lessons with photos of their favourite wrestler. If he can harness the power of Pokemon to teach a lesson, so be it. He meets kids where they are. This can include window dressing, like the wrestler, or working with the school or local librarian to find books that match the child’s interests and reading level at the same time. Parents can do this too.

For Emma Stewart, a Nord Anglia Teaching Fellow for Neuroinclusion who also works at St. Andrews International School in Bangkok, a bespoke approach to learning can take on a more social aspect. She and a colleague run a program for students who face challenges socialising independently with peers. Every Friday night they go and do a fun, kid-oriented activity, like bowling. “I'm talking about higher needs children who have been too anxious to go into a restaurant; we can facilitate that and spend their Friday night with their friends,” Stewart said.

Be curious about your child’s interests and preferences. Support them at home, and make sure teachers understand them at school.

3. Practice using inclusive language, with the recognition that it’s not the same for everyone

Just as you probably help your child pick interesting books to read, select activities and experiences they’ll enjoy, and monitor their screen time, you broadcast your values and behavioural norms to your children by the words you use. Likely, those norms have changed a good deal since you were a child, and you may be in the process of trying to find a shared set of terms that describes your family, the learning challenges your child, or children face, and values you assign to learning. “Do it because I said so,” for example, does not motivate most kids and probably won’t motivate your neurodivergent child.

It’s crucial not to label learners using negative language like “slow,” “dumb” or “stupid,” and instead use neutral language like neurodivergent and the specific name of your child’s diagnosis.

This will vary from person to person. You will have to be open about what feels problematic, while also listening to other learners and educators who may have different opinions. For example, Neale says that the phrase “try harder” is particularly difficult for him, because it implies that the problem is with the child, not the system. A different person could potentially find that motivating.

Stewart, who works with many children who are non-verbal and who need more support than many other students at the school, says that she’s uneasy with the phrase, “higher needs” because it reinforces a culture of comparison between students, even though it’s meant to be practical. These preferences can be highly personal.

If your child is able to have this kind of conversation it may be useful to ask what language they like, how they like to get feedback and what they don’t like. Listen and incorporate it into your family’s unique way of communicating, and let their teachers know what you find.

Check in with your child. Ask whether specific language choices, interventions and experiences are working and differentiate between challenging and mismatched.

4. Normalise, normalise, normalise

Human development is not a competition. Yet touting standardised achievements, rather than individual triumphs, can define our relationships with our kids and with other parents. Talking about a neurodivergent diagnosis, with your child’s consent, can be powerful for your child, your family and for other families in your community. It creates an environment in which neurodivergent learners are normal. “You shouldn’t have to be brave,“ to talk about your child’s unique strengths and challenges,” says Stewart.

Sarah Battersby, a Nord Anglia Learning Support Teacher at the British International School in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam who is autistic and has ADHD, and who has neurodiverse children of her own points out that normalising different ways of learning and processing can relieve the stress of trying to blend in with everyone else. “Masking; when we try to appear ‘normal’ to fit in is exhausting, so we want to create an environment where everyone is accepted and not forced to be a square peg in a round hole,” Battersby says.

She doesn’t mean that we should ignore struggle, whether academic or interpersonal. Instead, she encourages parents and other educators to create moments for reflection. “It can be valuable for students, both neurodivergent and neurotypical, to describe situations that they have found challenging and to work in a small group or one-on-one to understand how the other person may have been thinking or feeling,” she says. “Teaching all children to…describe feelings and to find strategies to support the feelings can be extremely impactful, as can asking children how they feel, without judgement.”

Speaking openly about your child in a way that places them as one unique human in a community of equally unique, but different, learners, can help both your child and other parents.

5. Acknowledge and then let go of your grief around the diagnosis

Stewart noted that most parents, of all children, have hopes about who their child will grow up to be, maybe a doctor, a novelist, or a footballer. Most of them will be wrong. But for parents with neurodiverse children there can be a specific type of grief attached to a diagnosis. That grief, she says, is very real. “Sometimes the parents can think, ’Okay, they'll catch up,’ and then around year six, year seven, they're not [catching up], and then the parents go through a new grieving stage.”

“It can be quite challenging and it's different for every family and you just ride that process with them,” she says.

With some parents Stewart shares the prose poem “Welcome to Holland” by Emily Perl Kingsley, which takes the idea of a neurodivergent child as less than and reframes it into a different, and equally lovely, experience of parenthood.

Accept the sadness you feel that your child will face additional challenges in an already-challenging world.

Resources for parents of neurodivergent children

Experts and events

In the U.S., Dr. Edward Hallowell is a leading expert on ADHD. He has a podcast, is on TikTok and co-authored several books.

In the UK, Dr. Naomi Fisher focuses on autism, trauma and alternative routes to education. She teaches courses and webinars, and has written several books.

International Neurodiversity Celebration Week is from March 18 through March 24.

The International Dyslexia Association offers conferences around the world, suggests reading and research for parents and educators, and creates helpful fact sheets about dyslexia.

The Salvesen Mindroom Research Centre at the University of Edinburgh offers support for students, parents, schools and educators.

The Stanford Neurodiversity Project focuses on understanding the strengths of neurodiverse people through research, supporting neurodiverse university students and hosts a yearly conference.

Books and articles:

Wonderfully Wired Brains, by Louise Gooding is an introduction to what it means to be neurodiverse and the depth and breadth of the community.

Raising Human Beings, by Dr Ross Greene dives into how to support children who may be seen as behaviourally challenging.

Dr. Russell Barkley has written many books about understanding ADHD. He also has a YouTube channel.

The Real Effects of Using Negative Language with Kids, by Amy Boyington is an article that focuses on how to develop positive language in your home, and why that is so crucial.