We use cookies to improve your online experiences. To learn more and choose your cookies options, please refer to our cookie policy.

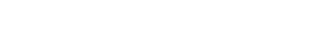

AT BISS Puxi, our fundamental approach is to encourage students to be 'Be Ambitious’. Aiming high, while getting the support of outstanding teachers and exceptional educational opportunities, increases your child’s chances of success.

MORE ABOUT ACADEMIC excellence