We use cookies to improve your online experiences. To learn more and choose your cookies options, please refer to our cookie policy.

Unlock a world of possibilities!

Join us on campus, meet our teachers and explore our learning spaces!

Mr Walter Gengel from the Astropeiler Stockert Radio Telescope and Victoria Fethke, a Year 13 BIS HCMC student, hosted an Astronomy Masterclass to enable BIS students to undertake hands-on research on topics at the frontline of science: dark matter and pulsars. Year 12 students live-controlled the telescope and measured the velocity of hydrogen clouds in our galaxy which reveal the existence of dark matter, thought to make up most of the universe’s matter. Moreover, they detected the period of a pulsar, from which the value of its unimaginably strong magnetic field can be determined. Victoria tells us more...

The Astropeiler Stockert is the first radio telescope in Germany and was initially used by the University of Bonn and the Max Planck Institute for radio astronomy research. Now led by amateurs, it still actively participates in research collaborations with universities in Germany and across Europe on topics including the pulsars, OH masers and Fast Radio Bursts.

The reason for the collaboration between this telescope and BIS HCMC stems from my research for my Extended Essay, the 4000-word research component of the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma. At the Astropeiler Stockert, I measured the Doppler-shifted Neutral Hydrogen (HI) emission line in the galactic plane in order to model our galaxy’s dark matter density variation up to 8.5 kiloparsecs (roughly 28,000 light years). This means that based on the motion of the inner galaxy, I found how much dark matter there must be and where its density is highest in the inner Milky Way. An article about this will be published in the VdS Journal für Astronomie this April.

After this research, I wanted to enable other students to have the same opportunity to undertake research. To make this happen, the Astropeiler Stockert Organisation developed a system to remote control the telescope from halfway across the world: Vietnam.

The students moved the telescope to a specific target in the galaxy and then instructed it to measure and analyze spectra of the HI (pronounced “H-one”) line. This is the name given to radio waves of frequency 1420 MHz which are emitted by Hydrogen atoms in our galaxy (when its nuclear and electron spin turn from parallel to antiparallel). By comparing the measured frequency with the rest frequency (its Doppler shift), the students determined how fast hydrogen clouds are rotating around the galactic center.

The surprising result is that the Milky Way rotates significantly faster than should be possible based on all the mass that we know of - all stars, dust and other bodies. To account for this, scientists theorize that there must be large amounts of ‘dark matter’, which we cannot detect electromagnetically and is probably made of matter that is still completely unknown to us. You can learn more about this by watching this video:

Next, students observed the period of the pulsar B0329+54, one of the most interesting objects in radio astronomy. A pulsar is a highly magnetized rotating neutron star and is formed at the end of a life of a giant star (about 10-30 times larger than the sun). After the star undergoes a supernova, the leftover core collapses into a size of only about 15 km in diameter, which pushes protons and electrons together to form tightly packed neutrons. In fact, the material is so dense that 1 teaspoon of neutron star material weighs around 10 million tons!

If that weren’t extreme enough, the pulsar’s magnetic field is a trillion times stronger than the earth’s. As pulsars spin (which can be multiple times per second), the pulsar emits powerful beams of electromagnetic radiation which are seen as a pulse when the beam is pointing to Earth. You can learn more about this here and here.

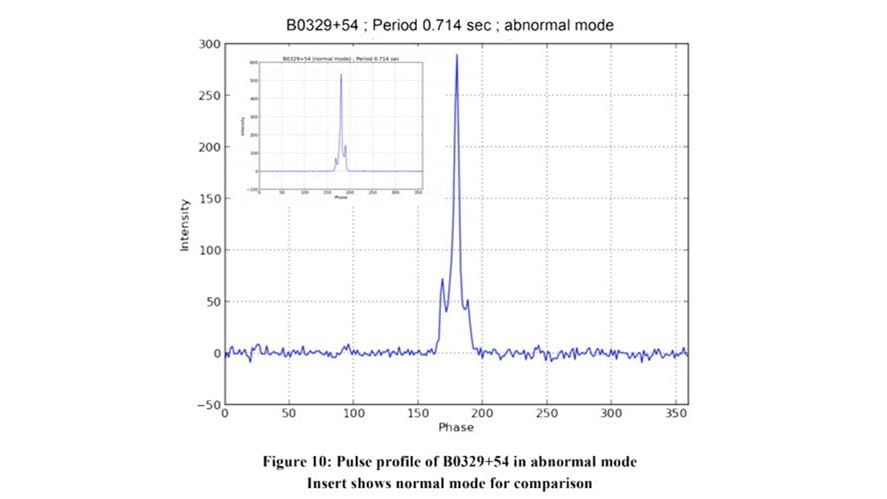

In our measurements of B0329+54, we could see that it has a pre and post pulse (small pulses before and after the main pulse), which so far scientists are unable to explain. Even more bizarrely, it switches from one mode into the other, which is also an active research area.

This was a very rewarding experience because it demonstrated, even as high school students it's possible for us to be involved in these exciting topics. Moreover, by learning about dark matter and pulsars, we realise just how much is still unknown about the universe but which, in the future, we could be part of disclosing.

Victoria Fethke, Year 13 IBDP Student